Greenwashing: The limits of ESG and impact investing

Impact investing promises to make our world a little bit better with sustainable financial investments. Can this promise be kept? What are the limits of impact investing and where does greenwashing begin?

Beyond Petroleum

Around the turn of the millennium, BP, the world's second-largest private oil company, hired global marketing agency Ogilvy & Mather and launched the "Beyond Petroleum" marketing campaign in 2000. On its website in 2004, BP provided a calculator that allowed anyone to calculate their own carbon footprint, "Find out your #carbonfootprint." The campaign aimed to establish the term "carbon footprint." The campaign was extremely successful, public authorities also put CO2 calculators on their websites, media wrote articles on how everyone can reduce their CO2 footprint, the campaign was crowned with an Effie award in 2007. Since then, we have all heard the term "CO2 footprint" or "carbon footprint".

But why did BP do this? The company's core business is the extraction of fossil fuels, mainly natural gas and crude oil, and this has not changed two decades later.

The campaign has been accused of steering responsibility away from petroleum companies and toward each and every one of us. Indeed, what is sophisticated about the campaign from the petroleum industry's point of view is that it suggests the problem can be solved with individual action. Such campaigns may create a guilty conscience and raise awareness of the issue, but they do not lead to any significant reduction in oil consumption – otherwise the campaign would never have been launched.

A brief history of CO2

Carbon dioxide, or CO2, acts as a greenhouse gas even in small amounts; it originates from volcanic activity as well as from asteroids. Our atmosphere consists of 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. The remaining percent consists of various other gases, among others carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide currently makes up 0.04% of our atmosphere.

This was not always the case.

CO2 is the nutrient for plants: from sunlight, CO2 and water, sugar (glucose) and molecular oxygen (O2) are produced in plants through the process of photosynthesis. Oxygen, in turn, is inhaled by animals and humans to oxidize it, simply put, with glucose, and we exhale CO2. Plant life and animal life thus form a CO2 cycle.

In the course of the earth's history, the proportion of carbon dioxide has fluctuated greatly, and molecular oxygen has also only been present in the atmosphere since photosynthesizing organisms took over. This event, known in Earth history as the Great Oxygen Catastrophe, led to the extinction of many anaerobic organisms of the time, for which molecular oxygen was lethal.

Part of the carbon bound by photosynthesizing organisms (animals, plants, plankton) in the form of sugar, cellulose and other hydrocarbons was deposited in sediments over millions of years (and transformed into coal, oil or natural gas in deeper layers of the earth) and thus removed from the CO2 cycle. Only modern man, in the course of the industrial revolution, began to lift it out of the ground again.

For several decades now, due to our extraction of fossil fuels, the CO2 content in the atmosphere has been rising slowly year by year, but very rapidly by earth-historical standards.

The question of whether we as a human race want to reduce our CO2 emissions into the atmosphere is neither an individual one, nor the responsibility of individual companies. It must be answered politically.

If we seriously want to reduce our CO2 emissions, there is no way around agreeing as a world of states and a global community to limit the extraction of hydrocarbons. We can spin it any way we want: we can either get the remaining coal, oil and gas reserves out of the ground, or we can get our act together. But we should agree on the price we are willing to pay.

History teaches us that global consensus is possible: In the 1990s, the international community succeeded in banning CFCs.

Lucrative margins for the financial industry

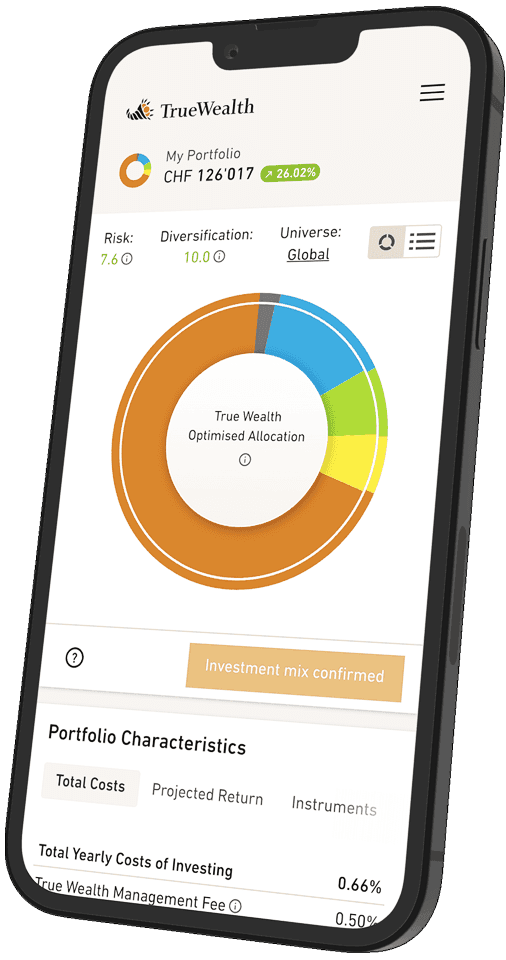

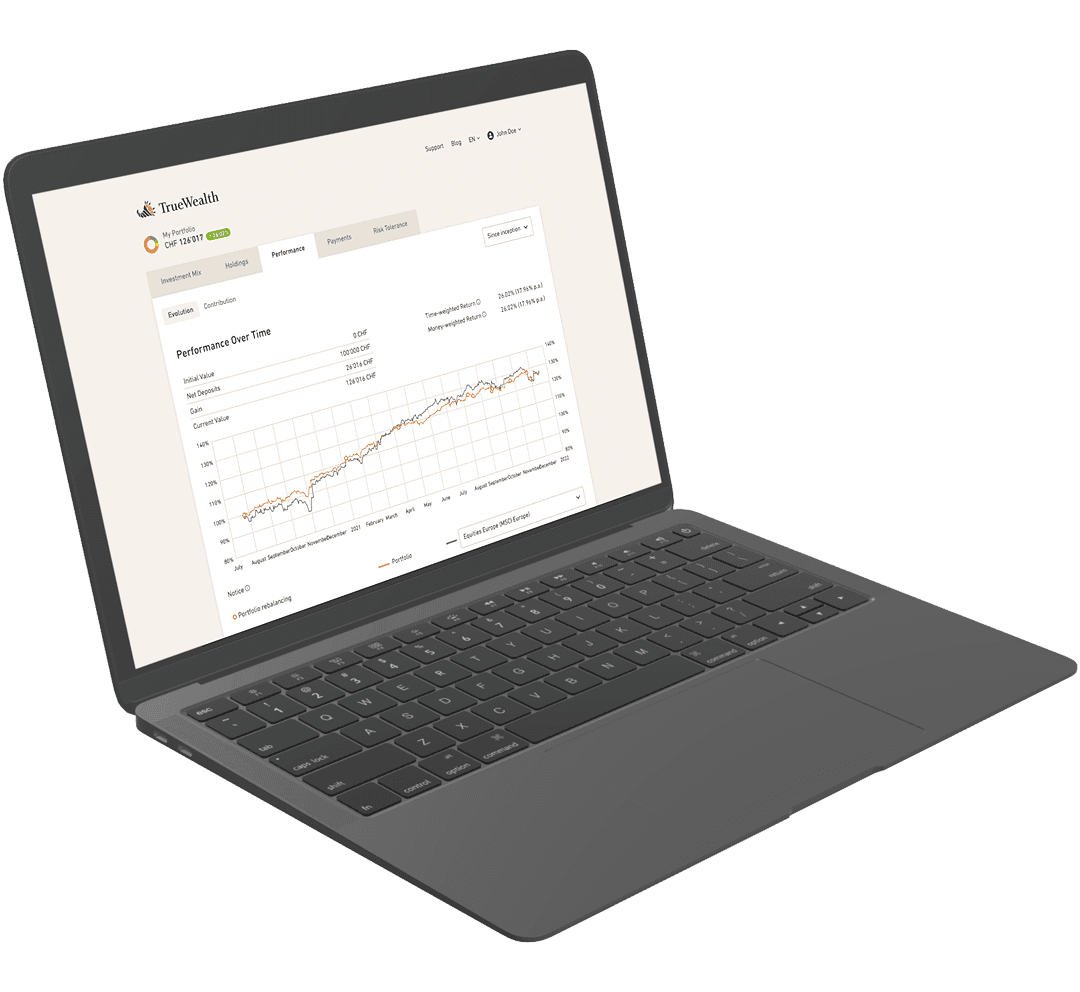

Recently, there has been a noticeable increase in the supply of and demand for sustainable investment products. At True Wealth, for example, around a quarter of new customers opt for a sustainable investment portfolio.

In addition to an appropriate financial return, many investors also want to ensure that their financial investments are compatible with their moral values.

Or is there more to it than that?

Until the turn of the last millennium, moral behavior meant that it was in accordance with the social norms and values, rules and commandments that apply in a society. A Catholic pension fund, for example, would not invest in shares of contraceptive manufacturers. The pension fund of a Protestant institution would perhaps exclude arms manufacturers in its investment guidelines. A Muslim investor would want to be mindful of the prohibition on interest rates in the Koran and not hold bonds in the portfolio (the financial industry offers these clients a Sharia-compliant substitute called Sukuk certificates).

Now something remarkable has been added: Almost all members of Western, secular affluent societies have achieved a historically unique level of security of supply in material terms. At the same time, religions in Europe are experiencing a rapid decline in membership. The Western model of an open society of free market economy, rapidly advancing technological progress and social equalization, which emerged from the Enlightenment, has lifted billions of people out of abject poverty and brought prosperity to many. Communist China, which also emphasized economic growth and technology but not democracy, equality before the law, and freedom of expression, has also seen its poverty decline.

But the need for meaning and togetherness remains. Religions are being replaced by new ideologies that also have the power to bind us together internally and to separate us from the outside world.

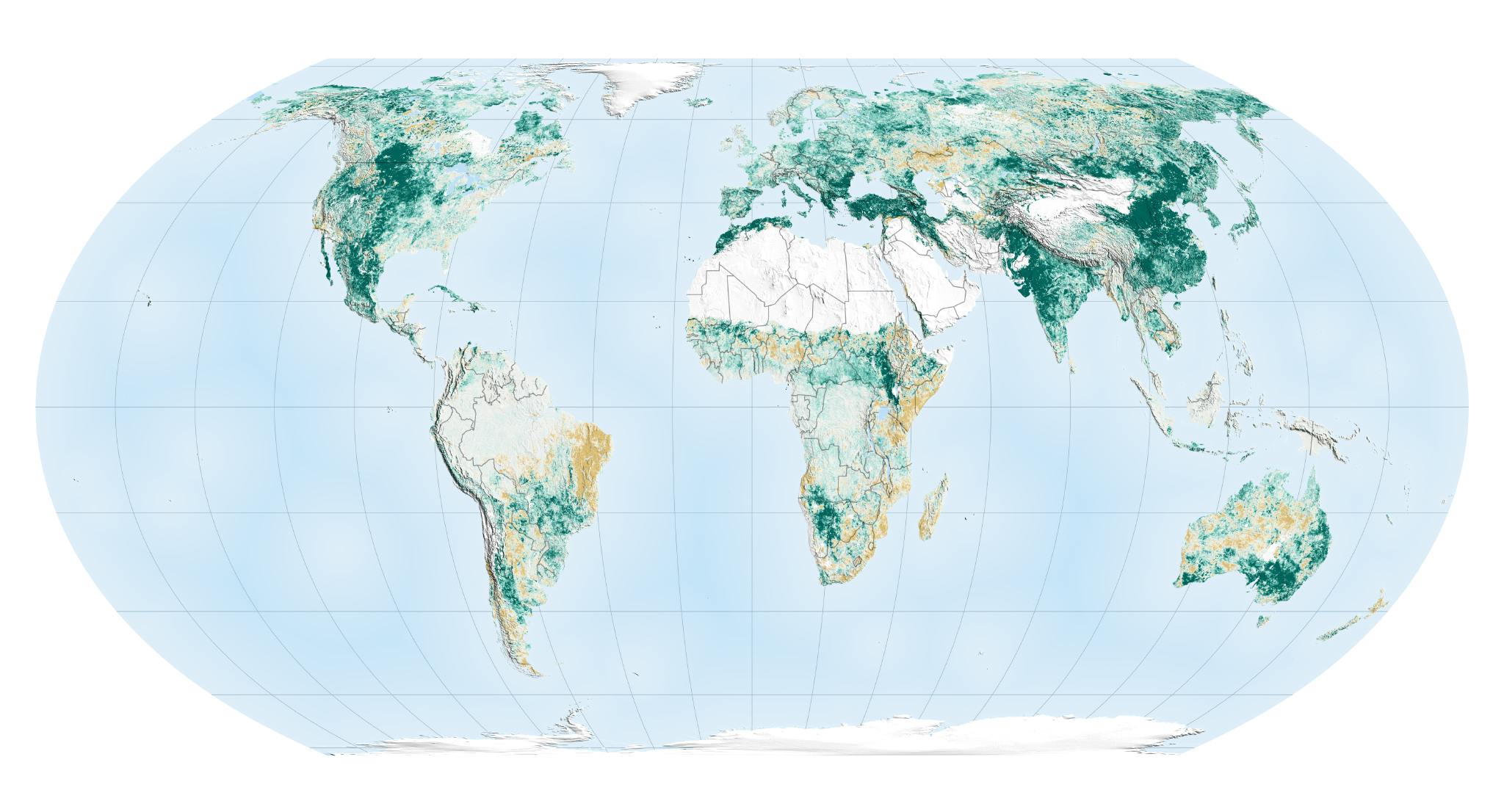

And there is something else: We are all slowly realizing that we humans have become the dominant species that is visibly changing and increasingly reshaping our planet. This is accompanied by new challenges for mankind: For example, we are steadily increasing the CO2 concentration in our atmosphere, although scientists warn that this increases the risk of irreversible global warming with consequences that are difficult to assess. But the interrelationships are too complex for the individual, and accordingly we long for simplification and guidance. The fact that a rising CO2 concentration could, for example, also lead to a greener planet (Greening of the earth and its drivers, Nature Climate Change, 2016) and to greater fertility and higher crop yields in certain regions is only mentioned here in passing.

C3 and C4 plants respond differently to higher CO2 concentrations

C3 plants and C4 plants have different metabolisms. C3 plants include wheat, rye, barley, oats, potato, hemp, rice and soy. C3 plants respond positively (assuming temperatures remain constant) to increasing CO2 concentrations. C4 crops such as corn, millet, sugarcane, and amaranth, on the other hand, respond less or not at all to higher CO2 concentration. However, the temperature optimum of C3 plants is about 15 to 25 degrees Celsius, while C4 plants thrive optimally at about 30 to 47 degrees Celsius. This biological fact will cause winners and losers and does not make finding political solutions to reduce our CO2 emissions any easier. The question of how the combination of higher CO2 concentrations and accompanying rising temperatures will affect C3 photosynthesis is significant for global food security and is the subject of research.

But back to the topic at hand: The financial industry is responding to the need for meaningfulness and social change with investment products that are linked to the promise of generating a non-monetary return. And some investors may simply be dissatisfied with the speed at which a political consensus toward a sustainable economy is being reached and implemented at the national and international levels.

As a result, new terms have emerged in recent years, most notably ESG. The acronym stands for Environment, Social, Corporate Governance, meaning the consideration of environmental and social aspects as well as separation of powers in companies. Similarly, SRI stands for Social and Responsible Investing. A third sales label is impact investing. Banks and asset managers offer a wide range of sophisticated, quite sophisticated investment solutions to these buzzwords. Net zero and 1.5 degree Celsius investment portfolios are marketed. With a sharp tongue, one could say: financial companies are the saviors of the present.

And the journey continues, seconded by politics. So it's no longer just about climate change; an increasingly large part of the financial industry promises to use your money to promote a wide-ranging bouquet of 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

And in the EU, legislators have created an extremely complex body of financial market regulation regarding sustainability. The collection of laws is referred to as the Jungle by lawyers who deal with the subject matter.

In Switzerland, the Federal Council has followed suit, but with the "Swiss Climate Scores" for climate transparency in financial investments, it is (for the time being) relying on individual responsibility.

But for the financial industry, the desire for "sustainable investing" is a welcome need: The industry has always gratefully translated issue trends into investment products. But never before has investing been associated with so many emotions and sociopolitical creeds. It's a long-awaited opportunity to shift the focus away from measurable investment outcomes and cost transparency to something not measurable, ultimately underpinned by subjective values.

This allows the financial industry to again increasingly sell elaborate investment processes, so-called "active asset management" to broad investor groups, after Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe showed in 1991 that low-cost passive (i.e. index-tracking) investment strategies, which invest market-weighted in the entire market, inevitably lead to better investment results on average than more expensive active ones. The subsequent triumph of index-based ETFs began to take away sinecures from the financial industry that, from the industry's perspective, it now needs to recapture.

A brief history of the «Active Asset Management»

- 1612: The first stock exchange is established in Amsterdam, shortly after the founding of the Dutch East India Company.

- 18th century: The New York Stock Exchange is established at the beginning of the century, and a stock exchange is also established in Philadelphia. At the turn of the century, a stock exchange is also established in London (1801).

- 1896: The Dow Jones Industrial Average Index is created. It initially consists of 12 companies.

- 1926: An original version of the S&P 500 Index begins to track 90 stocks in a stock index.

- 20th century: Mutual funds are introduced to the market, allowing anyone to participate in the market with relative ease, without having to worry about choosing individual stocks themselves. However, mutual funds are expensive.

- 1990: The first ETF (Exchange Traded Fund) is created in Canada. First used by institutional investors such as pension funds, private investors soon recognize the benefits of ETFs.

- 1991: Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe publishes "Arithmetic of Active Management" in 1991.

- ETF volumes explode, see The ETF Boom: Growth for All

This brings us to the question: What is promised with sustainable investing?

First promise – higher returns

Some market participants promise higher returns with sustainable investing. But higher than what? The benchmark is understood to be a market-weighted comparative index that invests unfiltered in all securities of a market. The securities are weighted according to their (freely tradable) market capitalization. The argument of the sellers of sustainable investment products is that sustainable companies are better positioned for the future and that this is not yet sufficiently reflected in the share price.

However, any form of "sustainable" investing must inevitably deviate from the overall market and is therefore active management, whether it is rule-based and broadly diversified (as via best-in-class sustainability indices) or via individual, hand-selected stocks is irrelevant. I.e. it remains a bet against the aggregated market.

This brings us back to the return promise of active management, which Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe logically stringently exposed as false in 1991 (see box above).

To be precise: For every franc of investment capital that is "sustainably" (and thus actively) invested relative to the aggregate total market, there is somewhere a franc of "anti-sustainably" (but equally actively) invested. We will come to these anti-sustainable investors below. Strictly speaking, all we know for sure is that the market-weighted index-oriented investor will do better before costs than both active investor groups combined.

However, the assumption that "sustainable" investing leads to better returns also runs counter to the basic idea of the impact promise: After all, an excess return from an investor's perspective means nothing other than a higher cost of capital for the sustainably operating company. Which in turn would mean that the sustainable investor is exploiting a shortage of capital that sustainably operating companies face. It should come as no surprise that most providers of sustainable investment solutions have moved away from this selling point.

Second promise – less risk

Instead of promising an additional return, some providers of "sustainable" investment solutions suggest that their investments entail less risk.

However, return must always be measured in relation to risk, and this is nothing new. For example, it is relatively easy to build a low-risk equity portfolio of stocks that move less pronouncedly with the overall market, this is called low beta stocks. Such a portfolio will have less risk, i.e. it will fall less in adverse market phases. On the other hand, it will also increase less in value in upward phases. The ratio of risk premium per unit of risk is called Sharpe ratio (the same William Sharpe as above).

In principle, one could lower any portfolio to a lower risk level by adding cash, or leverage it to a higher risk level by borrowing. In doing so, by definition, the Sharpe ratio does not change. However, this also makes it clear that the risk promise is nothing more than a return promise in disguise.

Third promise – «impact»

The sales argument that providers of sustainable investments are now increasingly using is that the sustainable financial product has a positive, non-monetary impact on the world.

This brings us to the essential question. Can sustainable investing have a positive impact, so that my investment makes the world a better place, at least a little bit, and changes it sustainably in my sense?

To make sense of the question, consider the following: The shares of most major companies are traded on the stock exchange. Worldwide, there are the equivalent of about 100 trillion Swiss francs. In addition, there are bonds issued by companies and sovereign debtors amounting to approximately 120 trillion Swiss francs. These are essentially, along with real estate and commodities, the liquid investment opportunities (one also speaks of public markets). Exchange-traded stocks and bonds together therefore account for about two to three times the annual global economic output.

Now, one could also invest in illiquid assets. Company investments that are not listed on the stock exchange are referred to as private equity. However, successful companies that reach a certain size will sooner or later find their way to the stock exchange, because above a certain size, the costs of a stock exchange listing are no longer important and the advantages of daily tradability outweigh the disadvantages from the point of view of investors and owners. This is why the liquid market of exchange-traded shares worldwide is about 8 times larger than the illiquid market of private equity. An investment in private equity is per se illiquid, i.e. it is not possible to exit the investment for many years, or if so, only at a large discount.

For most private investors, the liquidity of their investment portfolio is indispensable, since life circumstances can change at any time and one wants to have the capital available in case of emergency. For pension funds the situation is slightly different, larger funds can estimate their liquidity needs for years to come due to the law of large numbers; but even pension funds usually only invest a single digit percentage in private equity.

Reputable asset managers therefore invest the client funds entrusted to them by their private clients as diversifiedly as possible and, if not exclusively, then predominantly in liquid securities, i.e. in particular in shares of exchange-traded companies.

How "impact" investing works

If the investment strategy is to take sustainability aspects into account, stocks are not only selected on the basis of their risk and return characteristics, but the companies are also evaluated in terms of certain sustainability criteria and some are excluded from the investment universe.

How ESG investment funds work

In an ESG investment fund or ESG ETF, companies are ranked according to their sustainability score: The good ones in the potty, the bad ones in the jar. Only the companies with the highest score end up in the sustainable portfolio. In a best-in-class approach, this filter is applied separately in each stock market (regionally) and in each industry sector. This is in contrast to the Best-in-Universe approach, where the filter is applied globally. The best-in-class approach has the advantage that diversification across different industry sectors is maintained. However, companies remain in the portfolio that would be classified as unsustainable solely on the basis of their business sector. The best-in-universe approach, on the other hand, has the advantage that only the companies with the highest sustainability score are invested in, even if certain industries may not be included in the portfolio at all.

For example, index provider MSCI offers a best-in-class ESG index family that excludes 50% of the equity universe and a more stringent index family marketed under the SRI label that excludes 75% of all stocks. At True Wealth, we prioritize ETFs in the sustainable investment universes that follow the stricter SRI index (in addition to the best-in-class approach, certain controversial sectors, such as the defense sector, are also excluded). These indices, and thus the corresponding ETFs, are still diversified across many companies and sectors, and their returns are also generally similar to their traditional counterparts. But if you go further, and hold only a very small number of companies in your portfolio, you as an investor forfeit the benefit of diversification, at least in part.

Single and double materiality

ESG scoring, which is used in sustainable investment products to select portfolio companies, is based, among other things, on companies' sustainability reports. New terms have emerged here:

Single materiality provides for companies to report how sustainability issues impact their business.

Double materiality requires companies to report on both how sustainability issues impact their business and how their business activities impact society and the environment.

As obvious as it may seem, even if a sustainable investment product takes into account ESG scores in the sense of double materiality, it cannot be concluded from this that there is an impact connection for the investment product, an impact through the investment.

This brings us to the core question: what is the impact on our planet and our society when a growing number of investors exclude certain stocks, let's call them dirty or frowned upon stocks, and instead overweight others, let's call them sustainable stocks, in their portfolios?

What "impact" investing does

Looking at it in the light: The impact of sustainable investing is the opposite of what "impact" suggests.

First, we need to understand that company shares are usually not bought on the primary market (IPO), but on the secondary market, i.e. on the stock exchange. In other words, the seller of the shares is not the sustainable company, which thus receives additional capital, but another market participant who acquired the shares before us as sustainable investors. So for an "impact" to occur, we have to assume that this sends a signal to the market so that sustainable companies can expect more favorable capital costs the next time they raise funds.

But this brings us to the second problem, which is more serious: If more and more capital is invested by investors (with thoroughly noble intentions) in shares of sustainable companies, the average price of all sustainable shares will rise, and the average price of all other companies will fall. And this is exactly what would be wanted: sustainably operating companies would be rewarded with a lower cost of capital, which would inevitably lead to the desired result that more and more companies – due to the preference of the sustainable investor group – would invest more in sustainable projects. In this case, there would be an impact, a positive effect, and the world would become a better place as a result of my investment decision guided by ethical goals.

But: lower capital costs for the company also mean lower returns for the investor, these are two sides of the same coin. If you want to have an impact, you have to want losses in your financial investment return. Anything else would be a contradiction in terms.

Well, many investors who associate non-monetary goals with their investments would be perfectly willing to give up part of their return. The only thing is that such a state of affairs cannot last long in liquid markets. After all, in liquid markets, any market participant, no matter where he or she is, can buy or sell any security at any time. But the world is not only populated by altruistic people. For all those pursuing more mundane goals, an arbitrage opportunity presents itself, i.e. a financial advantage on a silver platter, as if cash were lying on the street:

For market participants primarily concerned with their financial returns, and there are more than a few of them, the less sustainable, the "dirty" companies will be the more attractive choice, because as long as they have a higher cost of capital, because ESG investment vehicles and sustainable investors leave them out, they are bound to have a higher return. But even if shares in "dirty" companies were socially frowned upon, and banks and asset managers completely excluded them from all the portfolios they manage, only one thing would happen: the excess return would be siphoned off by an even smaller group of market participants, but that would be all the more profitable for them.

This does not even require very many such profit-oriented investors: because a professional investor who is interested in this systematic excess return of the frowned-upon shares can skim it off with comparatively little risk input. It's not particularly costly technically, either: He or she buys a diversified basket of shares of the frowned-upon companies (the criteria for this are, after all, publicly known) and hedges the market risk by selling futures contracts on the entire stock market. For example, via futures on the S&P 500 or the SMI, which are highly liquid.

Now, the more private investors and pension funds shun the stocks that are frowned upon, the more returns jump out for these investors who step into the breach. This reduces the return differential between sustainable and frowned-upon stocks until equilibrium is reached (the cost-of-capital differential reaching equilibrium can be calculated and is very small for fundamental reasons, see The Impact of Impact Investing, Berk and Binsbergen, 2021).

As long as trading in frowned-upon stocks is not globally banned, such an equilibrium will always be established. However, such a ban is likely to be futile, as the political price would be too high. Otherwise, politicians could have banned the frowned-upon business as such, for example the production and import of fossil fuels.

Third, and here is the rub: The more investors invest according to ESG criteria, the more those who do the opposite are financially rewarded. This ultimately provides financial support to interest groups that can invest some of their excess returns on lobbying to maintain the lucrative status quo, such as state licenses for coal mining.

The sales pitch that sustainable investments in liquid assets have a particular positive impact is tempting, but ultimately greenwashing.

Is the future doomed? Let's not throw out the bath with the baby: Investing more generally has a fundamentally positive impact on society, because investments create factors of production to meet human needs.

A political consensus is needed for the rules of the game as to what companies may and may not do in this context; this cannot and must not be delegated by politicians to the world of finance.

What could be done

Maybe it wouldn't be so difficult. Let's take the E (Environment) in ESG and the challenge of global warming as an example.

In the early 1980s, scientists noticed that a hole in the ozone layer was forming at the South Pole. Stratospheric ozone protects us from strong UV radiation. The cause of the ozone hole was CFCs in refrigerants, spray cans and insulating foams. In 1987, the international community agreed to a ban on CFCs in the Montreal Protocol, and at the turn of the millennium the hole in the ozone layer was closed again for the first time. If the international community remains disciplined and individual countries do not pull out, the ozone layer in the Arctic and Antarctic will be able to recover completely in the next few decades.

Certainly, the CO2 problem is more challenging than CFCs, but again, there is no solution short of political consensus. It needs the political will to limit CO2 emissions if we want to do so.

It would therefore be time to have an honest political debate about whether the costs and uncertainties of global warming are greater than the costs of preventing it, and whether we want to bear those costs, and how we want to distribute them. The answers to these questions should be democratically legitimate. To be sure, these questions are not easy, because higher CO2 levels in the atmosphere will not only make our plains warmer and sea levels rise. It could also lead to higher crop yields in some areas, while other regions will become barren, small islands flooded, and coastal regions struggling with rising sea levels. But one thing is certain: uncertainty about climatic conditions on Earth is increasing, and humanity will have to adapt.

But if our answer to both questions is yes, we should begin to leave the remaining fossil fuels in the ground, first coal as the most CO2-intensive energy source, then oil and gas as well. Even if an immediate stop is politically unrealistic. But step by step, with binding restrictions for the future.

As an aside, one alternative often mentioned is to sequester the CO2 produced by fossil energy production, i.e., to pump it back into deep layers of rock and store it there. Relying on this could be dangerous, as it is likely to prove more costly than energy efficiency gains and the transition to non-fossil energy sources. Either way, both will make energy more expensive. This makes it all the more important that we shape the framework in a clear and binding way, without politically prejudging the best technological and economic solution.

And provided we decide as a community of nations to transform our lives away from cheap fossil energy and toward a CO2-neutral economy: The most efficient solution for this from an economic point of view already exists, we are just shying away from applying the instrument consistently until now: Cap & Trade. This means that the world of states agrees on how much CO2 may be emitted into the atmosphere each year in the future, and allocates emission certificates for this, which can be traded on the stock exchange. Imports from countries that do not participate will be subject to a tariff so that goods associated with CO2 emissions do not undermine our efforts. If we make this binding over a longer future, with decreasing certificate volumes over the coming years to net zero CO2 emissions, risk and growth capital will flow into new solutions and technologies, entrepreneurs, scientists and engineers will find ways to get there. Certainly, this will make energy significantly more expensive for all of us, at least for a longer period of time. And we would have to be prepared to cut back.

But the power of human innovation almost cannot be overestimated. If we have the political courage to set the right framework conditions, we will also find solutions to future challenges.

Greenwashing through sustainable financial investments is not part of the solution. It takes the courage of politicians and society not to delegate a problem to the financial industry that it cannot solve.

What does this mean for me as an investor?

Let's not be fooled by the promises of the financial industry. ESG investments can make perfect sense if they make your investments more compatible with your ethical principles. However, keep a healthy degree of skepticism about the promises of salvation made by the financial industry. Especially if investment products are supposed to suggest an impact. This applies not only, but especially to investment solutions that invest in liquid markets.

Sustainable investments, ESG and impact investing are especially good for the financial industry because they almost always carry a higher price tag. Even at True Wealth, the cost of the external investment instruments we use (known as the Total Expense Ratio, or TER) is slightly higher in the sustainable investment universe.

However, our own fees and margins are the same whether you choose the sustainable or the global (i.e. market-weighted) universe. This allows us to work for your investment objectives free of conflicts of interest.

About the author

Founder and CEO of True Wealth. After graduating from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) as a physicist, Felix first spent several years in Swiss industry and then four years with a major reinsurance company in portfolio management and risk modeling.

Ready to invest?

Open accountNot sure how to start? Open a test account and upgrade to a full account later.

Open test account