Talk – What is the current state of social mobility in Switzerland?

What does economic literacy mean, and why is it central to direct democracy and social mobility in Switzerland? A conversation with economist Dr. Melanie Häner-Müller.

Ms. Häner-Müller, you combine economic analysis, socio-political thinking, and commitment to education policy. One focus of your work is economic education, or, as you call it, economic literacy. What is economic literacy and why is it important?

Well, broadly speaking, it is actually the ability to see economic connections in everyday life, to have economic knowledge, and to be able to apply it.

Financial literacy, the classic financial knowledge that is typically part of economic literacy, is probably better known. But economic literacy goes beyond that. This can perhaps be illustrated well using the example of an interest rate. When it comes to financial literacy, you need to know what an interest rate is, how to calculate it, and perhaps also growth, compound interest, and so on.

When it comes to economic literacy, however, you might want to know: «How is such an interest rate actually determined? What does it have to do with monetary policy? Why does it change at all?» This may sound abstract, and you may ask yourself: «Why do you need to have this extensive knowledge if you're not an economist?» But in Switzerland, with its direct democracy, this is extremely important because most referendums have economic implications. That's why it's so important for citizens to be informed and to know and understand the overall economic concepts and basic principles.

So does that mean that economic literacy is almost a prerequisite for direct democracy?

Absolutely, yes. And the two are even somewhat interdependent. In a direct democracy, where people often participate in initiatives and vote, they also take a greater interest in economic issues and are better informed. In other words, there is a bit of a mutual influence. We know, for example, that people with higher economic literacy are more likely to vote, i.e., they are more interested in it and perhaps more confident about putting a cross on the ballot paper. So it's very, very important for direct democracy and not just something for economists.

What about social mobility in our country? Is Switzerland socially mobile?

The simple answer is yes, it is. To put it in more complicated terms: if you ask yourself what influence your family background has on your own income, you can compare siblings, for example. In economics, the parent-child relationship was often considered in the past, which is also important, but siblings are even better suited for comparison. This is because siblings share many things that go far beyond parental influence. For example, they attend the same school and may have similar circles of friends and social networks.

We looked at how much family background contributes to income in Switzerland, and the figure is 15 percent. We traced this percentage back to the 1980s. Over the last 40 years, it has remained very stable, averaging around 17 percent. Now, it is difficult to interpret what this 17 percent means. Conversely, it means that around 85 percent is not explained by family, but by individual characteristics. That is one thing. A comparison at the country level also helps: in the US, almost 50 percent is explained by family, and even in the Scandinavian countries, which are always considered to be very mobile societies, around 20 percent can be explained by family. This means that we are really at the top.

Wow, better than the Scandinavian countries?

Exactly, even better than the Scandinavian countries when it comes to income. But what you often hear – and it's true – is that «academic children» are often disproportionately represented at universities. People often say, «Yes, but that means that there isn't really equal opportunity in Switzerland.» And indeed, if you look at education, family background accounts for about 33 percent in Switzerland. That means that about one-sixth of income and one-third of educational success can be attributed to parents.

Now the question is: «How does that fit together?» Because if you look at the US, for example, it doesn't matter at all whether I measure social mobility in terms of income or education. Those who have a top Ivy League degree and have studied at the best US universities will later earn the highest incomes.

And those who don't have a university degree in France, for example, will have a difficult time?

Exactly, it's different in Switzerland. Among other things, this is really thanks to Switzerland's strong dual and permeable education system. That is really one reason why our income mobility is so high and why there are ultimately many ways to achieve a high income. Fortunately, much of this is independent of one's own family. As a researcher, I should perhaps describe something else we did as part of the project. We went back to the Middle Ages so that we could analyze 15 consecutive generations. And now, of course, you're wondering: «How exactly do you do that?»

We couldn't dig up tax data and reconstruct family trees going back to 1550. We looked at Basel and made use of a surname analysis. That is, who was enrolled at the University of Basel over the 15 generations? And what are the names of these people? This is fully documented, and the University of Basel is the oldest university in Switzerland. We then looked at the distribution of surnames in Basel society as a whole. We evaluated baptism and birth registers and looked at how surnames are distributed in society as a whole. This allows us to see, for each individual generation, how the elite is composed and how the general population is composed. This way, we can see which families were over- or underrepresented at the university. I have now run through this using the example of the university. We also worked with other data, such as guild data, certain tax data, and occupational information.

There was a large amount of data that we could use. It was actually quite simple: classic Basel names include «Burckhardt,» «Merian,» and «Faesch.» You can look at how many of the students, among the elite, have these surnames and how many there are in society as a whole. For example, if «Burckhardts» make up five percent of the students but only one percent of newborns, or in society as a whole. Then «Burckhardts» are five times overrepresented at the university.

However, we didn't just look at individual surnames, but really all of them that existed in each generation. It's very important to keep looking at this, because there is constant migration, which can loosen up and mix up social structures. We have also observed this over time. It's interesting that we have noticed a certain fluctuation in parental influence over the 15 generations. Mostly in times of crisis, war, cantonal separation, and so on, there was greater permeability, i.e., greater social mobility, and then it rose again. It's a roller coaster ride. After crises and wars, for example, we know that inequality usually decreases again and that opportunities for social advancement tend to increase again.

However, we were not only interested in the parent-child relationship, we also wanted to know how it affects subsequent generations. And that's exciting: grandparents account for about half of what parents account for, so they only have half the effect.

The effect of great-grandparents is no longer statistically detectable. We found this impressive, because there is a popular saying: «The first generation creates the fortune, the second may still be able to manage it, but by the third it is slowly becoming critical, and the fourth is no longer so successful.»

We call this Thomas Mann's «Buddenbrock effect.» It says that within four generations, family influence disappears. This also shows once again how permeable Swiss society is. It's a nice sign that it's not just about having the right last name, but that you have to work hard to be successful.

This is very important if you want to have a society with equal opportunities. Do you have a hypothesis as to why this breaks down after the third generation? Is it because family members no longer make the effort, or what do you think?

Yes, that's difficult to say. We look at all the data. It's quite difficult to pick out individual cases. What we do see, however, is that grandparents, for example, may still have direct contact with the younger generation. We also know, for example, that certain abilities may skip a generation and then reappear in the next one. For certain characteristics, it makes sense that there is still a certain connection with earlier generations. But since most people probably did not know their great-grandfather personally, an effect is unlikely there.

In other words, it is not enough to come from a wealthy family.

Yes, at least not in the long term. So you could say that it helps if you come from a wealthy family or a family with a high level of education, but the effect is not long-term. Three, maybe two generations at most, but no more.

Exactly, and that's why it's important to combine this with an understanding of the current situation. Economists would also say: «In the long run, we are all dead» – why should I care about that if my great-grandfather no longer influences me? I want to have intact opportunities for advancement today.

That's why we looked at what percentage of income can be explained by family background. And it's remarkable that it's only 15 percent. So even within these two generations, opportunities for advancement exist in Switzerland.

If we now look at today's wealth in Switzerland: how evenly or unevenly is wealth distributed?

Of course, it is difficult to compare income and wealth directly. The top 1% owns 40% of total wealth – not including pension fund assets.

However, we cannot compare these figures directly because income is a flow variable that is generated anew every year. Wealth, on the other hand, is accumulated and is a stock variable.

As I said earlier, the top one percent owns about 40 percent of total wealth. However, if we include pension funds – and these are only estimates – we arrive at about 30 percent for the richest one percent. That is significantly less than 40 percent. This is a special feature of Switzerland: for many Swiss people, their pension fund assets are the largest component of their wealth.

It is interesting to note that income inequality has remained very stable over the last 100 years. However, wealth inequality has increased. We saw a small increase in the 2000s.

How is this possible if income and wealth are linked?

Our research shows that wealth is a very complex variable. Inheritance plays a role, but it does not explain the increase in inequality.

The inflow of wealth from abroad—in other words, rich people moving in and thereby increasing wealth inequality?

Yes, exactly. When the attractiveness of a location increases, we have more wealth. This in turn leads to more high wealth and thus to greater wealth inequality. That explains about one-sixth of this change.

Another important component is stock market performance. That is the big difference we have seen now. It is not capital income such as dividends – otherwise it would be visible in income inequality – but rather a change in book value.

In times of low interest rates and expansionary monetary policy, there was an increase in book profits. As a result, a large part of these profits can be found on the capital market. This is an important reason, as is the associated rise in real estate prices. This means that wealth and wealth concentration are much more complex and multi-layered than just income distribution alone. To become wealthy, you need income. But the factor, i.e., the question of whether to invest in stocks or real estate, is crucial.

This brings us to the next topic: retirement provision. As I said, if you add pension fund assets to the equation, the inequality in wealth is significantly lower. This means that, especially with regard to capital market developments, it is extremely valuable that we have a strong second pillar in retirement provision in Switzerland. This allows lower income groups to participate in capital market developments.

Can you give a rough estimate of the size of the second pillar, for example how much capital it contains, or its ratio to economic output?

Yes, it's very impressive: we have 152 percent of our economic output in pension fund capital. We are among the top performers, but we are not at the top. The Danes, for example, have 192 percent of their economic output in pension fund capital. If you look at neighboring countries, the figure is 11 percent in France and 7 percent in Germany. That is really almost nothing. That is the big difference that we have with our strong second pillar.

The question of consumption versus investment applies at the individual level, but also at the level of an entire country or economy.

Exactly, that's very important. That's the first aspect. The second aspect is the broadening of wealth. In other words, different income groups can also build wealth. We see that it is important to be invested in order to build wealth. Exactly, and that's where we have this constellation with the second pillar. There are essentially three contributors: first, the insured themselves, i.e., the employees; second, the employer; and third, the capital market, which acts as a third contributor with the compound interest effect when the contributions are invested over many years. This brings us back to financial literacy. The effect is important in the long term.

Left-wing circles are known to prefer the pay-as-you-go system, as we have with AHV, where nothing is saved. The money earned by the working population is paid directly to pensioners. This is in contrast to the pension fund system, in which capital is invested. What would be the consequence of a pure pay-as-you-go system?

I believe that from an overall economic perspective, it must be said that retirement provisions must always be financed from the current economic process anyway. The funds have to come from somewhere. That is why financing does not play such a big role, but it does play a very big role on the distribution side, which you mentioned. If you look at a pure pay-as-you-go system, such as our current AHV, then of course we have completely different distribution effects. This is because we have a system that is unique in Switzerland with uncapped AHV contributions. We pay AHV contributions on our entire salary, but a maximum of around 2'500 Swiss francs per month is paid out.

So those who earn well subsidize the AHV.

Exactly, they pay a kind of tax on the portion that is no longer credited to their pension. This means that we have much more redistribution in the first pillar. This is important because that is also the idea behind the first pillar: to secure people's livelihoods. This redistribution is necessary here. The idea is that even people who, for example, had no earned income still have a certain level of security.

But if you look at the second pillar, you see that everyone saves for themselves and participates in the capital market. If we were to expand the first pillar, we would have a lot of problems. Firstly, we would no longer have the same investment potential, because it would simply be shifted from the active generation to the retired generation.

This means that the entire return on the capital market can no longer be reaped because people are not saving over a lifetime. That is an important point. Secondly, we also have demographic change.

There are more and more elderly people. Today, the ratio is approximately one to three. This means that one pensioner is financed by three young people. We expect this ratio to be one to two by 2050. This is another aspect where it is naturally easier to organize this using a funded system, so that everyone can save for themselves and use the capital market as a third contributor.

The redistribution you mentioned, which is built into the AHV through the capping of payout amounts, is actually a redistribution of income, not wealth, right?

Yes, that's right, and what I mentioned is even before any redistribution. We looked at the tax redistribution effect, which further reduces inequality. If you include the AHV, you see an even greater reduction in inequality, because AHV contributions are effectively like a tax on higher incomes.

Can financial and economic literacy help to reduce economic inequality?

There are actually studies that show the link between inequality and financial literacy. Especially when I talk about economic literacy: pension literacy actually explains a big difference in retirement capital. This is important because it is a skill that you should have from the outset if possible. If you don't have it, you end up with path dependencies, so to speak, because you miss out on the compound interest effect over years or decades, which creates larger gaps. This means that, in terms of income and wealth inequality, it is desirable for people to have economic and financial literacy.

Do we need a new school subject that promotes financial literacy?

I think that if you look at the timetables, there isn't much room, but it's certainly a good idea to integrate it. That is also the aim of the various curricula.

How much can I save or invest? This is how you introduce young people to these concepts as early as possible. Youth debt is a big issue. It is important to know from the outset how much money you have coming in and how much you are spending. To know what it means to buy something on credit and to ask yourself whether financing a motorcycle or car makes sense, or whether it would be better to wait a little longer. And once you can afford the motorcycle, the car, and the big vacation, you should perhaps also consider saving or investing certain amounts. It's best to start as early as possible. But this is not just a school issue, it's also a private matter. You gain your first experiences with pocket money. You realize, «Ah, if I put this aside, I can buy more.»

Ms. Häner-Müller, that was very interesting. Thank you for talking to us. Thank you to our listeners and viewers: see you next time.

About the author

Founder and CEO of True Wealth. After graduating from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) as a physicist, Felix first spent several years in Swiss industry and then four years with a major reinsurance company in portfolio management and risk modeling.

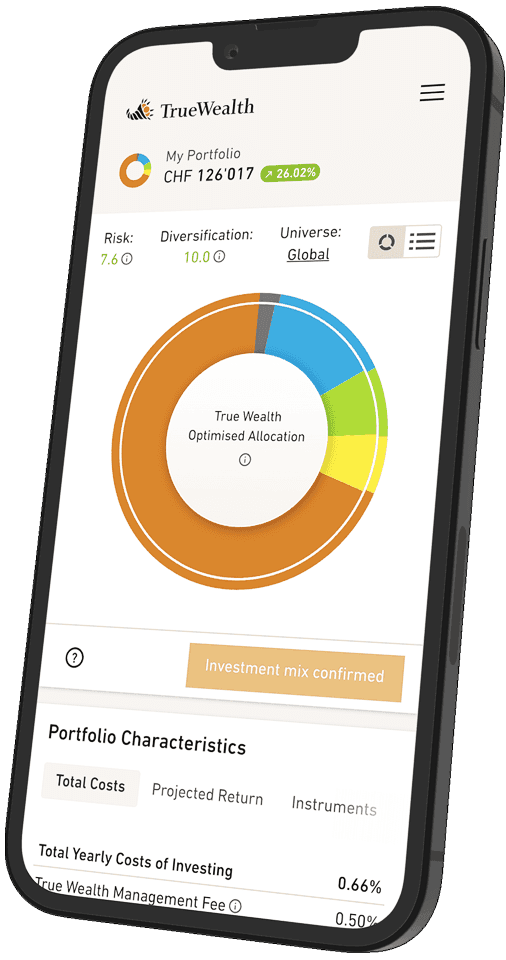

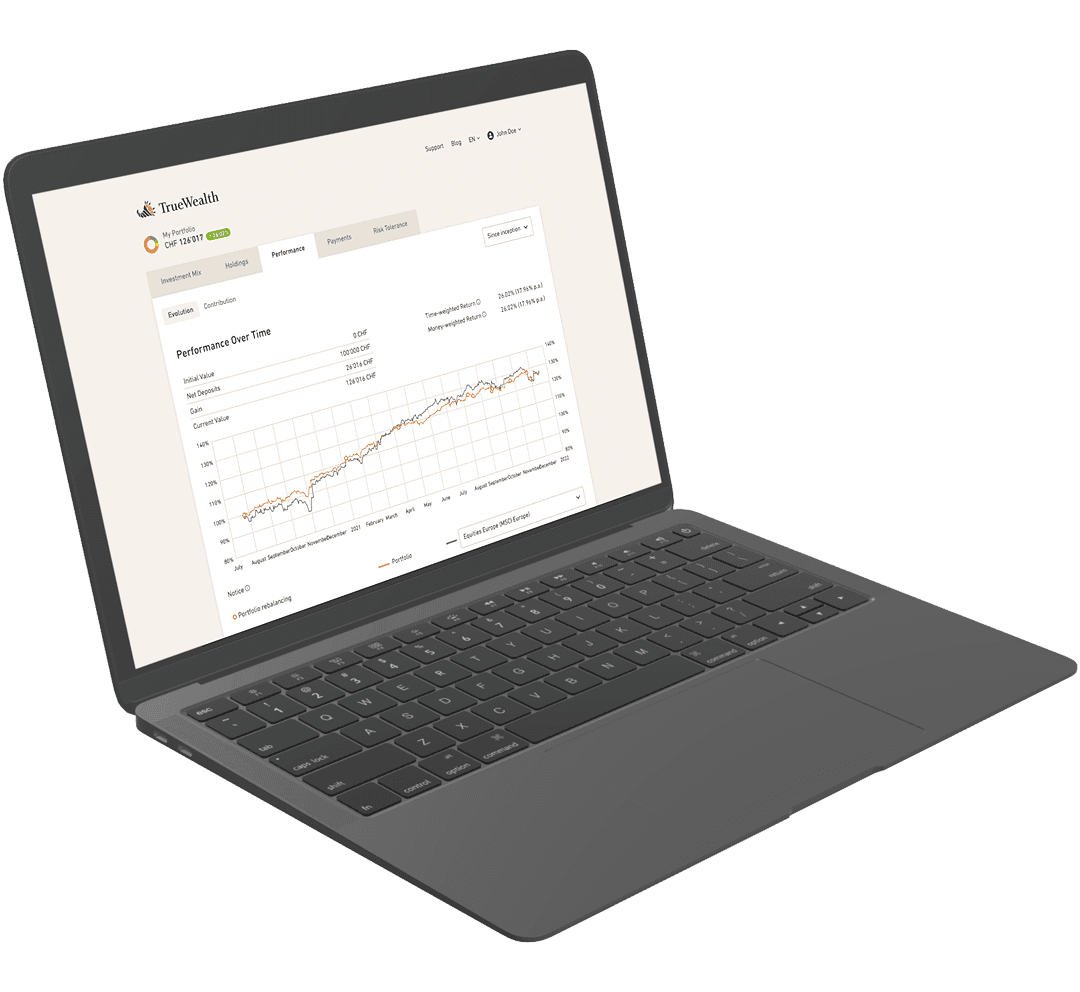

Ready to invest?

Open accountNot sure how to start? Open a test account and upgrade to a full account later.

Open test account